.jpg)

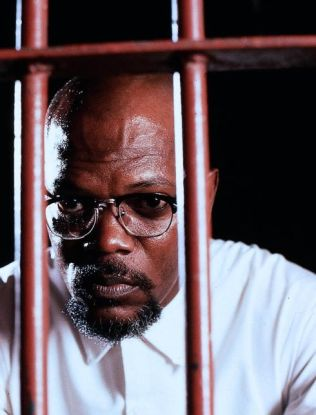

Note: Sam Jackson is wearing a hat for the Birmingham Black Barons, a Negro League team that played 1920-1960.

Tonight I'm headed to the TCG "Our Stories" Gala honoring Samuel L. Jackson and LaTanya Richardson Jackson, whose long and often interconnected careers in theatre, film, and television have culminated in the current Broadway revival of The Piano Lesson, which Richardson Jackson directed and in which Jackson appears as Doaker. It's something of a full circle moment for both of them: Jackson originated the lead role of Boy Willie in the play's Yale Rep production in 1987, then understudied it on Broadway (Charles Dutton starred), and Richardson Jackson has directed a number of plays by August Wilson over the years, though this is her first staging on Broadway.

Nearly 30 years ago, in one of the first issues of the actor's magazine I founded in L.A., we featured a long "actors' dialogue" with the couple, who had only fairly recently settled in L.A., ostensibly for her TV career, though they ended up staying to support his then-about-to-explode film career. This was well after Jackson was a regular presence in films, including in a few memorable roles in Spike Lee films, but about 7 months before Pulp Fiction's release made him a film icon.

As this frank, wide-ranging conversation makes abundantly clear, though, these were at heart two veteran theater artists still figuring out the ropes of Hollywood, with clear eyes and no illusions but a real openness to the next turns in the road. I think it's safe to say these two figured it out, but it's also great to have them both back on the stage (I say both because while Richardson Jackson has been no stranger to the theatres as an actor, both regionally and on Broadway, her husband hasn't trod the boards for more than a decade.)

And btw, if you haven't seen Piano Lesson on Broadway, what are you waiting for? I commend to you Helen Shaw's rave review to get a sense of what you're missing.

Here's the whole dialogue as it appeared in 1994.

Back Stage West March 3, 1994

ACTORS' DIALOGUE: Samuel L. Jackson and La Tanya Richardson

On Stigmas, Soaps, and Actors Named Ice

We didn't bring Samuel L Jackson and La Tanya Richardson together for this dialogue; they've been together for 24 years, first as New York actors pounding the theatre boards and doing commercials, now as L.A. actors shopping for the piecemeal employment of film and TV. Jackson has two films on the way—Fresh in April, and Quentin Tarantino's Pulp Fiction in the fall. Richardson is set to direct a play in Minneapolis next month, and appear in the upcoming Angie. For us, they appeared recently at Jerry's Deli in Encino.

Sam: Being in California's been kind of different. I don't know, when I first started coming out here, I guess after Jungle Fever, it was exciting, strange in a way, going to meetings, talking to people I hadn't been able to talk to or I guess hadn't had access to for a while. It's kind of strange thinking that acting in my head was one thing, and acting in theirs was another. Figuring out the standards, being totally different from the standards in New York—we discuss that all the time, in terms of how we evaluate how we're doing as actors. In New York, we did it by the number of plays we did, the kinds of plays we did…

La Tanya: Who you got to work with.

Sam: I found New York to be a lot more nurturing in terms of actors, egos, careers, and opportunities to work with different kinds of people. Way back when we first got to New York we had the opportunity to work with Morgan Freeman and Gloria Foster, and being in the same arenas with those people and watching them grow, it sort of gave me a standard for learning how to work I used to kind of academically go through the stuff I was doing. I guess I did it for a long time, having an intellectual understanding of the material and not an emotional understanding.

La Tanya: I think you had an emotional understanding, but I didn't know what your investment was. Your dissection of the material was always so technically complete that it never bled into how you felt about it. It was always, "This is how it is, because this is how it should go." It's almost like you could read the writer's mind and technically break down exactly the way he said it, exactly the way he meant it, exactly the way the director was going to take it And generally you were right.

Sam: For a long time, that's what I thought acting was. I mean, it was acting, so it was about pretending to have those emotions and pretending to look a certain way or have the right expression at the right time or having the right vocal inflection. I didn't realize for a very long time that I was supposed to feel that way on stage.

I used to be real confused by people who say they "got lost in the moment." I was like, "Hey, I want you to be in control here. lf you're going to hit me, I don't want you to be so lost you're really going to hit me." I was real confused by what that all meant for a long time.

But you've been acting since you were a child, and I didn't start until was like grown, in college. So you had another kind of yardstick, through Georgia Allen and all those people that you worked with, Diana Sands, watching people like that when you were still in your formative years. Your understanding of it was totally different from mine, and for a long time, it was really an indictment of how I went about what I went about doing.

La Tanya: True, which is why more people know your name. When we walk in some place and they say, "And who are you?" I have to say, "I'm the housekeeper, and the mother"—

Sam: And the critic.

La Tanya: I’m the critic, I’m the one who knows everything, and they don't pay me for that. I came out here to do a television show, though, which is how I got to California.

Sam: Which is how I got to California.

La Tanya: You moved out here for me, and everyone thinks it was because of you.

Sam: But having said all that about this TV show, how do you find the correlation between how you feel about acting and how people deal with you as "TV actress"? Because you know and I know there's a stigma about television actors, and that people tend to pigeonhole you.

La Tanya: There's a stigma about black actors.

Sam: Well, yeah, but if you're a black TV actor, what does that mean?

La Tanya: It means that basically you're supposed to be very, very funny and fat.

Sam: And fat!

La Tanya: The fat part I usually can get to; I can do that very easily. I’m not always funny, because sometimes my politics end up getting in the way of my humor. My humor becomes biting and sarcastic such that they say, "That's not the kind of funny we're talking about." I haven't been categorized yet. I've got a couple of great movies under my belt and some nice little parts.

Sam: Yeah, the kind of things you used to refer to, in terms of me, as these things that aren't very large, that don't amount to a hill of beans. You used to always give me real problems about doing these roles. "Why don't they give you a bigger role?" and I kept telling you they were all part of leading to something larger, that would give me the experience to do what I needed to do when it was time for me to do it.

La Tanya: Now that's what I do, and because of you I have hope. I am the first to admit you were right. I wasn't trained that way, all I knew was theatre and the love of it, and I knew great theatre. So I didn't understand the movie process. I loved movies, but I didn't understand that you didn't have to dwell in a moment.

Sam: That they don't have time for you to dwell in that moment.

La Tanya: You know, Academy Award nominations have just come out. I grew up loving the Oscars, and watching all that was part of the why-I-love-the-business thing. It wasn't until you were so totally involved in it, when you won the award at the Cannes Film Festival for Jungle Fever and our lives changed totally, and people thought of you as this other person, that the awards became something else. They weren't just fun anymore, they became this thing, and I actually found myself being affected by them in a way I hadn't before. Then, when you weren't nominated for an Oscar for that—I was just so totally thrown by it that I've been boycotting them.

But now Larry Fishbume and Angie Bassett have been nominated, so we'll probably watch their category, but I won't watch the awards. I'll watch the beginning because Whoopi's hosting. I might have to watch all of it this year, now that I think about it.

Sam: Amen, amen.

La Tanya: Well, they're black and I'll watch anything black people do. I'm so starved to see black people do anything that I'll watch the Academy Awards to see it. I like good people to win, to get good things. So then, I guess I'm saying the Oscars are good things. They're noticeable things. And out here in California, it’s a résumé. A complete résumé.

LaTanya Richardson, at left, with the cast of the short-lived Frannie's Turn.

Sam: It becomes part of your commodity. I’m kind of confused at this point, because you try not to believe your press and what people say about you so you can keep your feet on the ground and be who you are. If I’m as good as everybody says l am, then why don't I have a job? One of the best lessons I ever got in this business was when I first got to New York I was being interviewed for Ragtime—you had to go in and do these interviews before you got to do an audition—and I was sitting there waiting and James Earl Jones came in. I assumed they were bringing him in there to offer him this role. Then I realized he was the best black actor of our time, in 1980, and he was sitting there being interviewed just like I was.

La Tanya: That's disheartening. You get a lot of that.

Sam: That was something for me to remember. As I sit wondering why I don't have all these offers, I remember that and I remember why. But it doesn't make me feel like I’m making any ground. I’m still being tested constantly. Even as these same people tell me how good I am, I still have to jump through the hoop. And when I do that, they put fire on it and raise it a little higher. It's not encouraging at all. But I still have my love for this business, and my passion for acting. A lot of actors claim they want to direct.

La Tanya: Like me.

Sam: I would like to direct a film, but I wouldn't like to sit in a little dark room with the same film for the next six months trying to put it together. Consequently, I have no desire to do that. I’m satisfied doing acting.

La Tanya: It's hard too for us because we are a family. It's us and our child and our life is not so centered around the business. It is and it isn't, because once we go audition or work, we come home to the house, and the school, and the school functions, the night of comedy we're doing at our daughter's school. When you're doing a television show, it gives you a sense of relief, to kind of know where you are. From day to day we don't know where we are or where were going to be. I’m not sure I like what television itself involves, but until you do a sitcom, you have no idea.

It's like with soaps. Until I did a soap I really didn't have the amount of respect that I do now for soap actors. It's a hard thing. You get up in the morning, you have a new script, you have to know it and be believable. I mean, it's a heightened sense of reality, but at the same time you have to believe that stuff when you're up there doing it. I tape the soaps now, they're such an integral part of my life. I could be embarrassed about the way I watch soap operas. I watch them late at night, going to sleep. I was doing a show in Mexico right before Christmas, and I made you tape every show while I was gone, for like 13 days. And when I came back I watched them all.

Sam: Thirteen days worth of four-hour tapes.

La Tanya: And did I learn anything? I think I did.

Sam: You learned who killed who…

La Tanya: I mean about acting. Acting in TV and film is different from the theatre. I still love the theatre best, because you can try so much.

Sam: I think it's the immediate gratification, the healthy exchange of real energy there. You're doing something and people are sighing, laughing, on the edge of their seats, and you can see them paying attention to you. In film, the energy exchange is not there. You just give and don't get anything back from the camera. I've been fortunate because most of the crews that I work with stop and watch the scenes that are going on and afterwards will say something.

La Tanya: I enjoy watching actors who I know study and have a sense of technique, who weren't just thrown in like standup comics…

Sam: Who spent time at their craft.

La Tanya: And knew that it was a craft and had a tremendous respect for what they were doing, and read books and knew what it took to get where they are. I like to read the books about how people have made it. I liked Laurence Olivier's.

Sam: And Michael Caine's book.

La Tanya: His book taught me what to do when I got in front of the camera, because nobody else did. In theatre, you get the technique as you train; there's the director telling what the idea is, where it’s going. Film, I find, is very singular. A lot of what you're asked to do you bring yourself.

Sam: I find it all to be a big game. You have to do some things to make filmmaking interesting, because mainly it's picture-taking. Most of it you're not talking, because the dialogue is not always as integral to the film process. Sometimes you’re walking, driving, peeking around the corner, picking something up. So you have to find ways to make it interesting. One of the ways that I found to make it interesting for me is to do things the same way at the same moment. We watch things and say, “That cigarette was longer before, that glass was emptier.”

La Tanya: That's just because we're into continuity.

Sam: But that's all part of it. If you're not playing that game then you're doing something wrong. Part of your job is to keep the illusion of consistency going.

La Tanya: I find it confusing to sit and think about where your hand was. I get lost in the moment, totally abandoning myself to the character. I didn't know what I was going to do, I knew why I was going to do it, which is what let me do eight performances a week. Now, in trying to do it in California, I don't find there's a great sense of respect for theatre. California's about Hollywood and the movies. You just finished doing a play, Distant Fires, and people were shocked about the quality of the theatre. Because I think here theatre had been an avocation, not something people did as a viable business, because you can't make money at it.

That’s the other thing, you have to make money. We have to support ourselves. This has always been my day job. I don't even know at this point what the competition is, because as a black actress I go to auditions with people who are 10 years my junior and 20 years my senior for the same role. It's confusing, to say the least. To borrow from Shakespeare, "To thine own self be true." You wake up in the morning and figure out who you are and go to an audition and hope someone will buy it.

Sam: Everything changed for us. We spent all that time building great reputations in New York for doing quality work, which was criterion number one when you walked into a place—the kind of work you were doing, the kind of commitment you had to the theatre, the kind of work habits you had. The quality and consistency of the work meant something. Now all of a sudden the number of tickets your last movie sold at the box office becomes the criterion. The number of people in Iowa who have a Nielsen box who watch your show becomes the criterion.

La Tanya: And whether or not you are a rap artist.

Sam: It has very little to do with the quality or consistency of your work; it has everything to do with the quality and consistency of the dollars that are associated with your name. And that's something that you as the artist have no control over. A lot of times it's the material, it's whoever is in that material with you, it’s all kinds of things that you don't even know where to start to assess.

La Tanya: When you look at it, what is your separate reality? Because they're white and they have a separate reality than ours. That's just the truth of it. So our perception of ourselves is so different from how others perceive us, and basically I have found that white people who run this business seem to feel that black people have to have this edge, this South Central edge all the time that a lot of us can assume; we know it but we don't have it.

The most normal black people are in commercials, because that is the only venue I have seen where you are portrayed as a normal person. But see, it has a stigma attached to it out here where you're not supposed to do commercials because then you're deemed a commercial actress. I haven't done a commercial since I’ve been in California. I miss it, because I liked doing them.

Sam: And luckily when you were in New York, doing commercials, it's what kept us alive. Because we were basically theatre actors, and we couldn't live on that.

La Tanya: You're not kidding.

Sam: I couldn't do commercials 'cause I did have that edge; commercial people don't want a black guy with a goatee and an edge…

La Tanya: Too tall, you were too tall.

Sam: But you've also been lucky…

La Tanya: I’ve been blessed. I've worked with some of the fiercest directors, from Mike Nichols to John Avnet to George Miller, the fiercest of the fierce.

Sam: They hire you to do these small parts and then say, “Well, look what we got here, we need you to do something else so that she could do something else,” and that speaks volumes for your ability as an actress.

La Tanya: Surely now I believe the industry should recognize there's money to be made in black people. Black people have to understand that.

Sam: They do know that, and that's why everybody who has Ice in front of their name is working, and we're not. People tend to do movies that are mindless and have rappers and comedians in them, they have singers in them—they have everybody except the people who spent time trying to figure out what the hell they were doing and how to correctly convey an emotion to the people that are paying their money to watch them do it. It's a sin and a shame.

La Tanya: I would like to have the luxury of just acting and not thinking about any of the other stuff that goes along with it.

Jackson in Against the Wall, directed by John Frankenheimer.

Sam: Also, it's like you were saying, I've met all these directors that were, like, so correct craft-wise. I got a chance to do a film with John Frankenheimer. Meeting that man and knowing all the things he's done, like knowing that he came from live television, where he directed over 100 live television shows, which is like doing theatre in a whole other venue for a whole larger audience, and which I watched as a kid growing up, you know the respect that he has for his craft. I mean, he knows so much about what he's doing that when the lights are right, he knows what lens to use without even looking at a camera, and he's not trapped by a monitor like a lot of these new directors I meet, and he allows the actors to create, and that's totally rare. I'm not real sure how the new film school has changed the idea of filmmaking or the kind of films that have been successful have changed the ideals of new filmmakers, because most of them now are less actor-driven, they're something else-driven—I don't even know what the something else is, but they're not actor-driven. Quentin Tarantino writes scripts that are actor-driven; even though there are a lot of things going on, they're still driven by the people that are doing them. The action doesn't overtake the cause, so the people and their relationships become more important than what's going to happen. That's why we respect the older films.

La Tanya: Yeah, I know, 'cause you could watch the people, not how exciting the explosion is or how devastating the mayhem was when the murder was committed, or how they got stabbed or how the gun was the pivotal point, or the point of the whole movie. That's blowing my mind. And it's something John Frankenheimer told us, too: Movies have always been made according to how much money they were going to make. It's just that there was a time when you did the movies that made the money but you felt a greater responsibility to make the movies that were going to be good films. And now you're not ashamed to say that the money is what's important. I need a lot of money right now. I'm trying to help build a school, so that's why I need a job. It's flowery for me to say I love acting, because I do love it. I just thank God I've been able to do it this long. I've been doing it a long time to not be famous.

Sam: But that wasn't the end-all be-all; that wasn't the point.

La Tanya: That was never the end-all be-all, but now I see that you have to want some fame in order to make the money, 'cause they don't want you if you're not famous.

Sam: I think I'm famous and you know how much money I make. So fame ain't the answer.

La Tanya: But it gets you through the door quicker than it gets me through the door. People say, "You're Sam Jackson's wife." And it's like, "Yes, should I put that on my résumé? Is that going to get me a job?"

Sam: It will get you a different kind of respect.

La Tanya: Yeah, right.

Sam: But actually, having done that play…

La Tanya: Distant Fires.

Sam: ...reminded me of why I was in this business in the first place. I mean, standing there every night and interacting with those guys, moving an audience and feeling them move, and hearing the response after the play was over, getting the satisfaction of each moment from those guys and just having so much fun moving that play along with those words.

La Tanya: To say that I just want to act for me at this point is simply a luxury that I can ill afford because you can't just act now. It's become so obvious to me that we are so interdependent on survival that you talk about acting and you talk about the business and it's almost like, "So what?" But it's an integral part of my life, so I've got to make it more than "So what." Because that's the way that I intend to make a difference somehow. It's the greatest medium in the world for reaching people, acting; people love it, it's a cause to celebrate. You know, we celebrate actors now more than we celebrate scholars, which is wrong in my opinion, but it's true.

Sam: Nobody's going to pay $7.50 to watch somebody solve a physics problem.

La Tanya: Yeah, but those people who are making enough money should pay the people who are solving the physics problem. I want somebody to figure out how to sustain buildings in an earthquake; we have a family living with us who were displaced by the earthquake.

Sam: Sometimes the things that we’re concerned with seem trivial in comparison.

La Tanya: But that's our only vehicle; it's what we think we know how to do.

Sam: We didn't take that other way out. Like my mom said, "What are you going to fall back on?"

La Tanya: Most of our mothers said that.

Sam: It never occurred to me to learn to do something else.

La Tanya: But we can do other things.

Sam: There's other things I can do, but there's no other viable way I know of to make a living.

La Tanya: There's no passion in the other way, because this is our heart's desire. I would like to do my heart's desire, which is to be an actress, a good actress, maybe even a great actress. I'm not going to stop trying to get there with each little thing. Yesterday I auditioned for something that was two pages in a 30-minute show. And half the world was there to get those two pages, but you pick yourself up and you go and when you don't get it, you go to the next page and the next two pages and you take it because you know it beats anything else I can think of, I guess. Nothing else would be as rewarding. Sometimes I think I should have done less edge work. I did a lot of edge theatre, a lot of avant garde, before it was called "performance art." The last play I did was a mixture of all that, Casanova, with Michael Greif. What a director! He's like Fellini to theatre, he has that kind of sight. To say he's a visionary now sounds overused; he had sight. He was conscious. He was clear, and he was imaginative. And that's why I think The Piano is doing so well. That woman… Women right now, because we've been so disenfranchised, are not afraid to tell an imaginative story. It's based in reality but has off-shoots of imagination, color, sight…things that are not so blatant. People might say, "That's too dreamy, that's not real, because it doesn't happen," but what does that mean?

Sam: It's about that reality-based stuff that you keep talking about. I didn't get a job because of that reality-based stuff.

La Tanya: Because you weren't real enough?

Sam: No, because I am real, and because the research that they're doing on the film told them there is no way that this woman could fall in love with a black man. "That's just not done." But it's a film. It's something they made up anyway.

La Tanya: And it's something that happens every day. It's just whether or not you're willing to take a chance on it being accepted.

Sam: I've been through that whole "It changes the politics of the film" thing. Indecent Proposal probably wouldn't have made as much money, but would have made a more interesting film to have me in it. If I offered homeboy a million dollars for Demi Moore—then you would have had an interesting story. You ain't got an interesting proposition with Robert Redford offering him a million dollars to sleep with his wife—so what? She might have slept with Robert Redford for nothing. But if you put me in that situation, or Morgan Freeman, or Denzel, or a Native American… The fact of it is, there's so many interracial relationships on this planet right now that the planet's threatened not to have any real white people left on it pretty soon.

La Tanya: And the interracial mix is not necessarily black and white; we've got to get away from that They ran away from it with Denzel and Julia Roberts, but we don't want to get into that.

Sam: Yeah, and Love Field didn't make any money. Spike couldn't even make it work for Wesley. A few people saw Jungle Fever, but it wasn't about that.

La Tanya: We need more Spikes. We need more of those twins, the Hughes brothers.

Sam: They're damn good filmmakers.

La Tanya: Out of all the angst that we've been bombarded with, it's amazing that we're still together after all these years, with such diverse careers—one down, one up, then one up, one down. I'd like to be there at the same place with you. Maybe one day soon, they'll say, "That's the great philanthropist La Tanya Richardson; she helped build a school. She donated all her earnings from the film ‘Blah’ to build a school."

Sam: Right, we'll get the credit line together.

No comments:

Post a Comment