It wasn't a one-on-one, alas, but I well remember the day I was ushered into a South Coast Rep rehearsal room for a sort of four-way interview: myself, another reporter, the press rep (Cristofer Gross), and Randy Newman, dressed in de rigeuer Hawaaian shirt. The occasion was a sort of revue of his work that music director Michael Roth and literary director Jerry Patch had cooked up called, after Henry Adams,

The Education of Randy Newman. It ended up being a creditable stage effort but nothing special (nor, by most accounts, was an eerily similar anthology evening at the Mark Taper Forum

just 10 years later). But I wasn't going to pass up the chance to talk to a songwriting idol, and after

Faust, which I'd enjoyed at La Jolla Playhouse, it still wasn't all the far-fetched a notion that he could write something worthwhile for the theatre. (More on that bittersweet subject

here and

here.)

Without further ado, this was my cover story for the magazine I ran at the time.

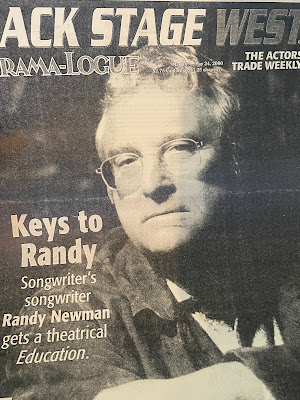

Back Stage West

May 18, 2000

Newman’s Own

Randy Newman writes narrative songs in character. Is it any wonder they're ending up on a stage?

by Rob Kendt

Does Randy Newman have an image problem? We're not talking about his unprepossessing looks, which he has jokingly compared in song to "froggish men, unpleasant to see.”

More damaging to the reputation of America's greatest living songwriter is his recent success as a sort of avuncular troubadour for baby boomers and their tykes, with the charming fluff he's written for such films as

Toy Story,

A Bug's Life,

Babe Il: Pig in the City, and, going back a few years to the beginning of this uncharacteristically benign period in his work,

Parenthood’s "I Love To See You Smile." It doesn't help his street cred that his two other biggest pop hits as a singer are "Short People" and "I Love LA." Nuff said.

While no one can begrudge a great artist some success and material comfort, in Newman's case this recent mellowing, which would include his distinguished career as an orchestral film composer, often threatens to overwhelm his enduring contribution to pop music: a 30-year song catalogue unparalleled in its acid wit, its supreme but unpretentious artistry, its unreliable but incisive storytelling.

This, after all, is the same songwriter who wrote "Rednecks,” satiric country anthem for Southern crackers that doesn't let the North off easy, either; "Sail Away," a sweet ballad which just happens to be a colonial slave trader's pitch to the Africans; “Wedding in Cherokee County,” the bluesy lament of an impotent circus freak, and such perverse confections as "Christmas in Capetown,” "Davy the Fat Boy," "I Want You To Hurt Like I Do." Even 10 years ago, the name Randy Newman was still a byword for double-edged character songs that were alternately moving, chilling, and hiarious—whereas now Newman and his patented ragtime shuffle are a family-friendly franchise.

His last album, 1999's Bad Love, even addressed his perceived irrelevance with the corrosively funny "I'm Dead (But I Don't Know It)" ("Each record that I'm making/ls like a record that I've made/Just not as good").

The mellowing is partly for real, Newman confessed in a recent interview at South Coast Repertory, where a new music-theatre piece has been fashioned from several of his songs, and is set to open June 2. Called The Education of Randy Newman, it's a sung-through musical conceived by SC literary manager Jerry Patch and musical director Michael Roth, with a Newmanesque central character carrying the evening from 1943 to today, employing Newman's character songs along the way to illuminate the personal and political upheavals of the period.

"The arc of it is, I learn that life is not so bad," said Newman of the show. "Which actually is something that I learned. I think I was a lot more unhappy at 24 than I am now. Maybe I'm just not paying attention.”

Not that he's disavowing his body of work—just that he's got more perspective about its rich, unsettling blend of misanthropy and compassion.

"I never had a horrible, bleak view of the world—I always knew that people were kinda decent. The people in the audiences who hear my songs are better than the people in the songs—they're exaggerations, I know that. I know it from talking to individual people—they're just not bad. It isn't like the world is a cesspool.

"I watched, on public TV years ago, Emile Zola's Nana, and it was the bleakest—it was like where you would go when you die. It was the worst, most depressing thing I've ever seen—way worse than life is, way worse. I just sort of knew that. It's that bad if you're a junkie; it's that bad if you're in love with someone who doesn't love you. But basically it's not."

Mixed Revue

The association with South Coast Rep, Costa Mesa's regional theatre powerhouse, began when Michael Roth, who had music-directed a straight revue of Newman’s songs, Maybe I'm Doing It Wrong, in the mid-1980s at the La Jolla Playhouse and Off-Broadway, suggested to SCR artistic directors Martin Benson and David Emmes another Newman revue. They were fans, and so was Jerry Patch—but he saw the possibility of more than a simple evening of tunes.

"I listened to a lot of his songs, and I had the notion that there something bigger than a revue here—that you coud tell a story with this material," said Patch. "Then the question became, How do you do that?"

Patch thought of The Education of Henry Adams, the 1918 classic by the Quincy Adams-descended historian—a droll third-person autobiography about the forces that shaped the 19th century, filtered through the unreliable but witheringly insightful lens of Adams’ experiences. With Newman's approval and editorial input, the South Coast team set out to weave some of his best songs into a narrative thread which, like Adams' biography, would not give an accurate portrayal of his life per se ("the details would be overwhelmingly boring," Newman quipped) but would present his uniquely alert, jaundiced point of view on his times.

His unique sensibility, both musically and thematically, is the product of his upbringing, mostly in Los Angeles but also, for a brief but significant period, in New Orleans, from whence his mother hailed. "I remember the ice cream wagon with the signs marked 'colored'—which was misspelled—and ‘white,’” said Newman. "I only lived there up to age three, but I went back every summer till I was 12." The new show extends this Southern sojourn a bit, in part so some of his Faulknerian songs about racists and con men and working-class anti-heroes can be included, and in part, as Newman explained, "so my character sees things which presumably give me my acute sense of social justice.”

Actor Scott Waara plays this Newmanesque central figure, and the rest of the cast—an illustrious troupe that includes Jordan Bennett, Gregg Henry, Sherry Hursey, John Lathan, Allison Smith, and Jennifer Leigh Warren—plays other characters who embody the personal and political upheavals of the past 50 or so years, in a sung-through evening directed by Myron Johnson.

"In many ways it's the most ambitious show we've ever done,” confessed Patch, who helps maintain SCR's deserved reputation as a bastion of literate new American plays. Indeed, while SCR has previously staged Happy End and Sunday in the Park With George, it is not part of the nonprofit regional theatre's Broadway tryout circuit, like its counterparts to the south, La Jolla and the Old Globe. In the context of SCR's literary bent, then, the collaboration with Newman makes perfect sense.

"Randy really speaks to us, 'cause he's dramatic writer," said Patch. "He brings aspects of theatre to everything he does. He's clever, witty, smart; he's got craft to burn. If we're going to do a musical, he's the guy to do it with."

Play the Playhouses

Indeed, as inevitable as it was that Newman would follow his illustrious uncles Alfred, Lionel, and Emil in the trade of writing and conducting Hollywood film music, it also seems inevitable that this master of character writing and narrative would set his sights on the musical theatre. And so he did, with 1995's Faust, a joyous if ungainly vaudeville pastiche of Goethe's immortal story which premiered at the La Jolla Playhouse and went to the Goodman Theatre in Chicago with a possible Broadway run in mind. (That hasn't yet materialized, and plans for a staging at the Kennedy Center went away with its outgoing president, Lawrence J. Wilker, who apparently still wants to mount it somewhere.)

Newman learned a lot from Faust—giving the audience a reprise or two, and giving songs a big finish so that actors can make a graceful exit, were two big technical lessons. He thinks it was misunderstood: "I believe I got too much credit for the songs and not enough credit for the book. The score wasn’t maybe as good as they said it was, and the book wasn't...I mean, compared to what? We weren't doing Shakespeare; it had a beginning and ending, more or less. And I didn't care: If I wanted to do a Busby Berkeley number—I really did—I did it, even if it didn't pertain to the plot.”

Above all, Newman seems to have learned to trust stage craftsmen with his material, especially the actor/singers who bring his narratives to life.

"| noticed with Faust that the actors made it better than it was on the page,” said Newman. "In Education, a number of the songs—the context and the performance is better than I can do; it's more effective.

"It’s like, movie actors you meet sometimes, they're disippointments somehow. It's not their fault, it's just that they're not 40 feet high and they're not real smart and graceful and everything. But these stage people—they sing, they sing in tune, in five-part harmony, they sight read. They do stuff I can't do. Besides being able to do a backflip and dance."

And he understands the value of working in theatre in an essentially pragmatic way: "One thing I did find out was that Faust, and I think definitely this show, played to people I could not play to. They wouldn't come to see me, and I couldn't keep 'em. Here you've got pretty people to look at, they're dancing around, some nice voices. Mv voice offends some people—music lovers—and once I get past 'You've Got a Friend in Me,’ Bug's Life, ‘Love To See You Smile,' and ‘Short People,’ I'm in trouble. But with Faust in San Diego and Chicago, they had kids, old black ladies, who liked it and sat through it, who I couldn't play for, really."

Of course, he dues play to an even bigger mass audience with his second career as a G-rated bluesman and film composer. But he clearly understands his place as a hired hand: "Every Disney movie I've done, I could have written the same song for: If we all pull together, things will work out." And film scoring lets him obsess on the craft of writing for orchestra, which he learned at the feet of his three composer/conductor uncles in Hollywood.

A show like Education, on the other hand, puts a new frame around some of his best songs for a mostly uninitiated audience. As SCR's Jerry Patch said, "Anyone in the Broadway business, or in music, knows how good this guy is. But to the general public, he's the guy who goes on the Oscars and sings the song from Toy Story. If this show can reintroduce his best songs to our audience—I think it will hit baby boomers right between the eyes."

It's Money That Matters

Still, Newman is not in any rush to write more for the stage. Not because he felt burned by Faust—his joy in that project shone through the score and still shows when he talks about it—but due to a more familiar dilemma.

"It takes years and there's no money—I can't afford it," he said matter-of-factly. "If I could earn a living doing it, it would be a good thing to do, 'cause I could use everything I know: I can write dialogue, I can orchestrate, write songs, write jokes."

The musical theatre might not want him, either, given his frank disdain for it: "It hasn't been the forum the best composers have gone into for quite a while; the best songwriters have been pop songwriters, for the last 30 or 40 years, mostly. Carole King and Paul Simon, people right there from New York, didn't go into it. There's Sondheim, but he's a lonely figure; everyone always has to say, 'Except for Sondheim.’”

His admiration for Sondheim is tempered by a slight but telling disagreement over rhyming.

"He was going to see this workshop of Faust that James Lapine was doing, and he said, ‘I hope you won't be nervous,’ and I said, ‘Well, I hope you don't mind a couple 'girl and 'world' rhymes.’ And he said, 'Well, I do, and you don't come from that [pop] place, either.’ And I said, 'Yes, I do. With the diction I have, I don't have to feel you can't rhyme...well, ‘girl' and world' is particularly egregious, but I've done it. Fats Domino rhymed 'New Orleans’ and 'shoes.' I don't mind that stuff, and Sondheim does. I don't agree with him.

"And sometimes I think he'll rhyme things out of boredom—just to show he can rhyme. He'll do a show about assassins or a murderer just because he has such virtuosity as a lyricist that he can do it. And yet, he's all we've got."

Newman, in person a sharp, funny, youthful personality at 56, stopped himself to realize: "I'll never get to Broadway—I've said so many bad things about things they love. It's like trashing someone's house before you see their house."

Indeed, after Paul Simon's famously contentious mounting of The Capeman in a hostile Broadway environment, Newman's comments may not get him a hero's welcome there. South Coast's world premiere of Education has no co-producers lined up to ensure it further productions; Patch said that the rights to the show remain mutually held by Newman and South Coast.

But while it's unlikely that the entire oeuvre of this songwriter's songwriter will ever get a huge popular embrace, South Coast audiences are likely at least to get a good survey course—an education in Randy Newman, if you will.